Station

Pointe Aux Barques, Michigan

Coast Guard Station # 248

|

Location: |

1/8 mile

souteast of Point Aux Barques Light, Lake Huron |

|

Date of

Conveyance |

1875 |

|

Station

Built: |

1875 |

|

Fate: |

Turned over to

the GSA in 1956 |

|

Station

Type: |

|

Keepers:

J.H. Crouch was appointed keeper in

1876 and left in 1877 (?)

Charles E. McDonald was appointed

keeper on 12 MAR 1887 and left in 1880 (?)

Jerome G. Kiah

was the keeper in 1880 who lost his life, along with his entire crew, on

23 APR 1880, on an attempted rescue. Click here for more information.

Henry Gill, Jr. was appointed keeper

on 9 JUN 1880 and transferred to [District] Station No. 3 on 28 SEP 1881.

Quinton Morgan was appointed keeper on

28 SEP 1881 and resigned on 14 SEP 1883.

Henry D. Ferris was appointed keeper

on 22 SEP 1883 and transferred to Station Sand Beach on 11 FEB 1898.

John H. Frahm was appointed keeper on

11 FEB 1898 and was still serving in 1915.

After the station was sold off it was

moved to the Huron City complex located to the west of the lighthouse and

south of Port Austin. This is a collection of historical buildings where

tours are offered during the summer months. The life saving station has

been preserved well and contains many artifacts and photographs of the

area. Hopefully the future will hold the same fate of preservation

accomplished here at other stations in Michigan.

Jerome G. Kiah

Gold Medal Awarded 8 November 1880

The gratifying record of so many human

lives preserved also has the sad obverse of loss. On 23 April 1880 the

crew of Station No. 2, Tenth District (Point-aux-Barques, MI), one of the

most gallant and skillful crews in the service, lost six of seven members.

It is the second time in its history that the establishment had had to

mourn the loss of a life-saving crew. The first instance was at the wreck

of the Italian bark Nuova Ottavia on the coast of North Carolina in

1876. This latter tragedy, however, had a great degree of uncertainty

regarding what caused the deaths of the crewmen. The Point aux Barques

disaster, on the other hand, is fully known through the evidence of a

single survivor, and the calamity in all its details can be recounted.

Nothing could be sadder than the story of this sacrifice. It is here given

in the report of the district superintendent, who immediately visited the

locality and investigated the circumstances.

"I arrived at Sand Beach the evening

of the 24th, and learned there that the life-saving crew were lost in

their attempt to reach a vessel in distress off their station, and that

the vessel had afterwards got out of trouble and was then lying at the

breakwater at Sand Beach. As the steamer on which I was going up was to

remain there a little while, I went out and saw the master of the vessel

and got his statement, which is substantially as follows:

"‘I am the master and owner of the

scow J.H. Magruder, of Port Huron. Her tonnage is 136.71. The crew

consists of myself and four men, namely, Frank Cox, Thomas Purvis, Eddy

Hendricks, and Thomas Stewart. I have my wife and two little children

aboard. I left Alcona with a load of 187,000 feet of lumber for Detroit at

noon the 22nd instant, wind north, fresh. Sighted Point aux Barques light

at ten o’clock that night, wind east, light, but breezing up. Took

gaff-topsails in at eleven o’clock. When abreast of light we commenced

listing bad to starboard. Saw we were making great leeway and the lee rail

under water. Discovered here, for the first time, that the vessel was

leaking badly, with two feet of water in the hold. About midnight was

laboring very heavy, with high wind and heavy sea. I feared we would roll

over, and was satisfied we could not weather the reef. Got both anchors

ready and let go about 2 AM the 23rd, when she immediately righted. Had

fourteen feet of water under the stern, and at every heavy surge on the

chains she would drag anchor, the seas breaking over her bows. Hung a red

light in main rigging, as a signal of distress to the life-saving station.

I certainly feared the vessel would be lost, and that our lives were in

great danger, if assistance was not rendered. The vessel would strike

bottom between every heavy sea. At daybreak I displayed my ensign at

half-mast, union down, and about 7:30 AM observed the answering signal

from the station. About eight o’clock saw the surfboat coming out. We were

about three miles southeast from the station. Lost sight of surfboat in a

few moments; thought the sea was too heavy for her, and that she had gone

back, but in about 1.5 hours (9:30) saw her again about one mile north of

us, pulling to the eastward, to get out of the breakers on the reef. In a

short time I saw her go down in the troughs of a heavy sea, and when she

came up we saw she had capsized. We saw them right her and bail out, when

she again started to pull for us. In about twenty minutes she again

capsized. Saw several men clinging to her, for some time, but finally saw

only one. Our boat was in good condition. She is 16 feet long. Did not

think of launching her. No ordinary yawl-boat could live in such a sea. I

thought the life-saving crew used good judgment in crossing the reef where

they did. I then commenced throwing my deck-load overboard, and at noon,

the wind shifting to the northeast, we made all sail and started, cleared

the reef, and arrived in Sand Beach all safe, but leaking badly. The

weather was piercing cold, and all that day the spray would freeze as it

came aboard of us.’"

The superintendent continues:

"I arrived at Huron City at one

o’clock Sunday morning (25th). The two dead bodies of surfmen Petherbridge

and Nantau were put aboard of the steamer here, and sent down to Detroit,

by direction of their friends. I arrived at the station at 3 AM, and found

Keeper Kiah in a very bad condition, both mentally and physically. The sad

story of his experience, and the loss of his brave crew, is as follows:

"‘A little before sunrise on the

morning of the 23d, James Nantau, on watch on the lookout, reported a

vessel showing signal. I got up, and saw a small vessel about three miles

from the station, bearing about east and by south. She was flying

signal-of-distress flag at half-mast. I saw that she was at anchor close

outside the reef. All hands were immediately called; ran the boat out on

the dock; and, when ready to launch, Surfman Deegan, on patrol north, came

running to the station, having discovered the vessel from McGuire’s Point,

1.5 miles north from the station. At this time a warm cup of coffee was

ready, of which we all hastily partook, and a little after sunrise (5:15

by our time) we launched the boat. Wind east, fresh, sea running

northeast, surf moderately heavy. We pulled out northeast until clear of

the shore surf, and then I headed to cross the reef where I knew there was

sufficient water on it to cross without striking bottom. ‘We crossed the

reef handsomely, and found the sea outside heavier than we had expected,

but still not so heavy as we had experienced on other occasions. After

getting clear from the breakers of the reef, the boys were in excellent

spirits, and we were all congratulating ourselves how nicely we got over.

I then bore down towards the vessel, heading her up whenever I saw a heavy

sea coming. When heading direct for the vessel, the sea was about two

points of the compass forward of our port beam, and for the heaviest seas

I had frequently to head the boat directly for, or dodge them. When about

a quarter of a mile from the vessel, and half a mile outside the reef, and

very nearly one mile from the nearest point of land, I saw a tremendous

breaker coming for us. I had barely time to head her for it, when it broke

over our stern and filled us. I ordered the boys to bail her out before

the sea had got clear of her stern, but it became apparent at once that we

could not free her from water, as the gunwales were considerably under

water amidships, and two or three minutes after she was capsized. We then

righted her, and again were as quickly capsized. We righted her a second

time, but with the same result. I believe she several times capsized and

righted herself after that, but I cannot distinctly remember. As near as I

can judge, we filled about one hour after leaving the station. For about

three-quarters of an hour we all clung to the boat, the seas occasionally

washing us away, but having our cork jackets on, we easily got back again.

At this time Pottenger gave out, perished from cold, dropped his face in

the water, let go his hold, and we drifted slowly away from him. We were

all either holding on the lifelines or upon the bottom of the boat, the

latter position difficult to maintain owing to the seas washing us off.

Had it been possible for us to remain on the bottom of the boat, we would

all have been saved, for in this position she was buoyant enough to float

us all clear from the water. My hope was that we would all hold out until

we got inside the reef where the water was still. I encouraged the men all

I could, reminded them that there were others, their wives and children,

that they should think of, and to strive for their sakes to keep up, but

the cold was too much for them, and one after another each gave out as did

the first. Very little was said by any of the men; it was very hard for

any of us to speak at all. I attribute my own safety to the fact that I

was not heated up when we filled. The men had been rowing hard and were

very warm, and the sudden chill seemed to strike them to the heart. In

corroboration of this theory I would say that Deegan, who did the least

rowing, was the last to give out. All six perished before we had drifted

to the reef. I have a faint recollection of the boat grating or striking

the reef as she passed over it, and from that time until I was taken to

the station, I have but little recollection of what transpired. I was

conscious only at brief intervals. I was not suffering, had no pain, had

no sense of feeling in my hands, felt tired, sleepy, and numb. At times I

could scarcely see. I remember screeching several times, not to attract

attention, but thought it would help the circulation of the blood. I would

pound my hands and feet on the boat whenever I was conscious. I have a

faint recollection of when I got on the bottom of the boat, which must

have been after she crossed the reef. I remember too in the same dreamy

way of when I reached shore; remember of falling down twice, and it seems

as if I walked a long distance between the two falls, but I could not have

done so, as I was found within thirty feet of the boat. I must have

reached the shore about 9:30 AM, so that I was about 3.5 hours in the

water. I was helped to the station by Mr. Shaw, lightkeeper, and Mr.

McFarland; was given restoratives, dry clothes were put on, my limbs were

dressed, and I was put to bed. I slept till noon (two hours), when my wife

called me, saying that Deegan and Nantau, had drifted ashore, and were in

the boatroom. My memory from this time is clear. I thought possibly these

two men might be brought to life, and, under my instructions, had Mr. Shaw

and Mr. Pethers work at Deegan for over an hour, while I worked over

Nantau for the same time, but without success. I then telegraphed to the

superintendent and the friends of the crew. The four other men were picked

up between 1 and 2 PM, all having come ashore within a quarter of a mile

from the station. The surfboat and myself came ashore about one mile south

of the station, the bodies drifting in the direction of the wind, and the

boat more with the sea. I ordered coffins for all. On the 24th, Hiram

Walker, of Detroit, telegraphed to ship the bodies of Petherbridge and

Nantau to Detroit, which I did, together with their effects. The other

four men were delivered to their friends, all residents of this county.

"‘The following are the names of the

lost crew: William I. Sayres, Robert Morison, James Pottenger, Dennis

Deegan, James Nantau, and Walter Petherbridge. Sayres and Morison were

widowers. Sayres leaves five children, the youngest eight years old.

Morison leaves three children, the youngest six years old. This would be

the third season for these two men at the station. Pottenger and Deegan

each leave a wife and four children, the youngest two months old each.

This was the second season for these two men at the station. Nantau and

Petherbridge were single men, and this was their first season at the

station.’

"Mr. Samuel McFarland makes the

following statement:

"’I am a farmer, and was working on

the farm about one-fourth of a mile from where the surfboat came ashore,

when I heard gulls screeching, as I supposed, several times, but paid no

attention to it. Presently my two dogs started to run for the cliff, and

thinking that somebody might be calling from the shore, I went to the edge

of the high cliff overlooking the lake, and saw a boat bottom up about 100

rods from shore, with one man on it. Not knowing that the station crew

were out, started to notify them of what I saw. Upon getting to the

station, about 9 o’clock, and learning that they were out, concluded it

was the surf-boat I had seen, and went to the light-house after Mr. Shaw

to accompany me to where the boat was drifting in. When we got there the

boat was ashore, and Captain Kiah was standing on the beach about 30 feet

from the boat, with one hand holding on to the root of a fallen tree, and

with the other hand steadying himself with a lath-stick, and swaying his

body to and fro, as if in the act of walking, but not stirring his feet.

He did not seem to realize our presence. His face was so black and

swollen, with a white froth issuing from his mouth and nose, that we did

not at first know who he was. We took him between us, and with great

difficulty walked him to the station. Several times on the way he would

murmur, "Poor boys, they are all gone." At one time he straightened out

his legs, his head dropped back, and we thought he was dying, but he soon

recovered again. Upon reaching the station he was given restoratives, his

clothes were removed, and he was put to bed. His legs from above the knees

were much swollen, bruised and black.’

"Mr. Shaw corroborates this statement

from the time he took part in it.

"I attended the funerals of Deegan and

Pottenger, the 25th, and hope I may be spared from ever again witnessing

so sad a scene. The wives of these two brave men were almost crazed by

their great loss, and the cries of the poor children left fatherless, were

heart-rending in the extreme. It is sincerely to be hoped that the bill

now pending in Congress, granting pensions to the families of surfmen who

lose their lives in the discharge of their duty, will become a law, so

that the families of these truly brave men may be compensated to the

extent of its provisions.

"In conclusion, I would state that I

feel very keenly the loss of this crew, but I can lay the blame at no

one’s door. It was one of those unfortunate accidents that are liable to

occur with the best of men and under the best management, but not likely

to occur twice in a lifetime. Had the boat been two seconds earlier or

later, the sea would have broken ahead of her, or she would have passed

over it before breaking; but upon straightening up the boat there was no

time left to back or dodge. The sea broke when she lay in the most

critical position to take it. Certainly it was the duty of the crew to

answer to the signal of distress, and certainly they responded most

promptly. There was no discord here; there was more than a friendly

feeling existing between the keeper and crew. They had together made a

good record at their station, and when duty called each strove to be

foremost in the boat.

* * *

"I have conversed with several who

have served with Keeper Kiah, and all speak in the highest praise of him

as a man, and of his superior skill in handling a surf-boat. He has the

sympathy of the entire community, including the friends and relatives of

his dead crew, in his present trouble."

The closing incident in the Point-aux-Barques

tragedy was the resignation of the stanch keeper, too shattered in mind

and body, for the time at least, to retain his position. Thus the heroic

station was by a day’s experience left at once vacant of its crew, who,

this very year, had saved nearly a hundred lives.

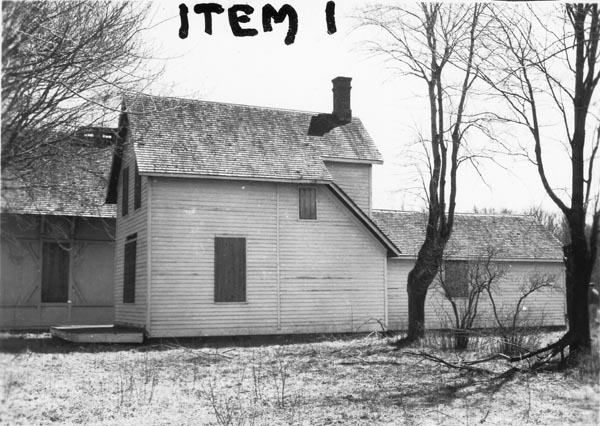

The end of an era, the old station boarded up, abandoned and thrown

away. Luckily when it was sold from the government it was saved. Today it

is fully restored and sits proudly in Huron City on display for all to

see.

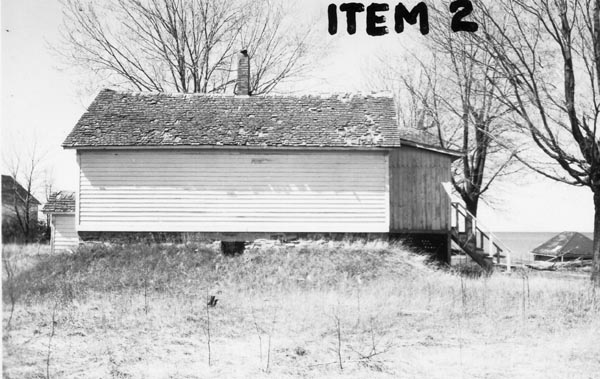

Side view of the abandoned station.

|

|

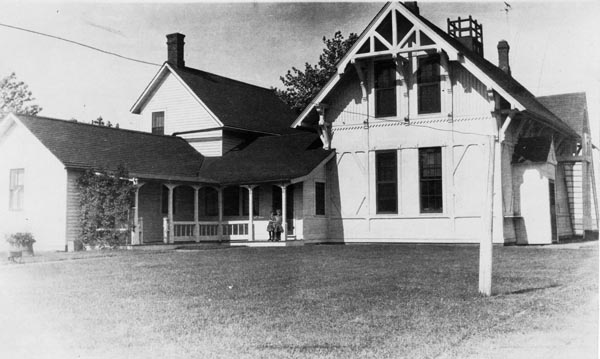

Close up rear view of the station house.

Further away shot of the rear of the station after the road was put in.

Rear view of the station house complex.

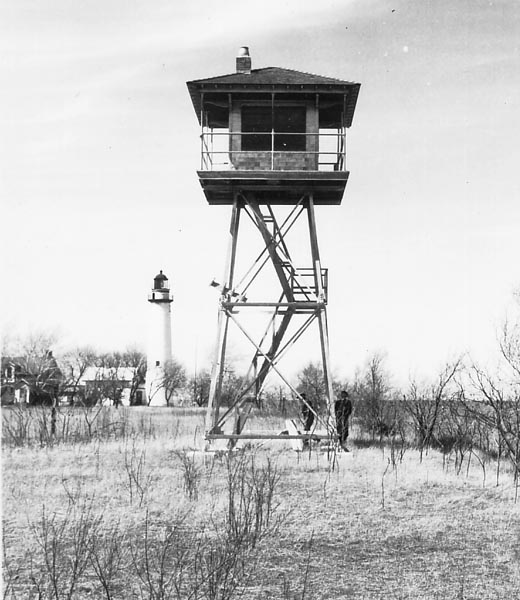

A view toward the lighthouse from the lookout tower.

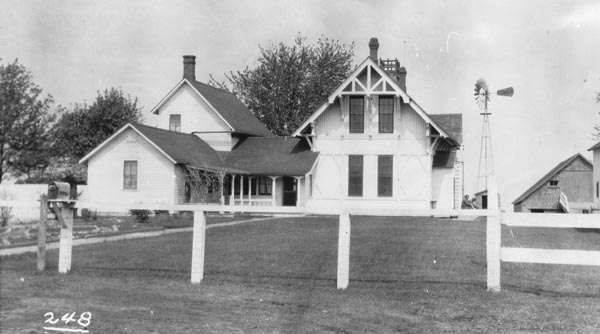

An earlier shot of the station with windmill.

Close up of the boat house, carpenters shop and station. Notice there is

no windmill present in this shot like the one above.

A front view of the station. 1925 photo.

Close up of the boat house and carpenters shop.

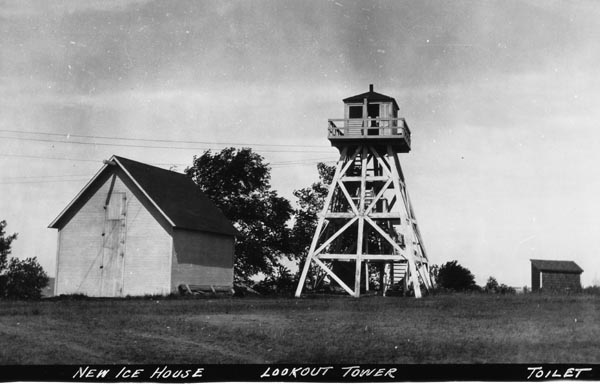

Old lookout tower with the newly constructed Ice House.

The old original

lookout tower.

The newer lookout tower.

The ice house in later years, note the lookout tower is no longer present.

The surfmen's houses

Close up of one of the surfmen's houses.

Surfmen's housing.

The abandoned barn.

Crews dormitory in ruins. |